|

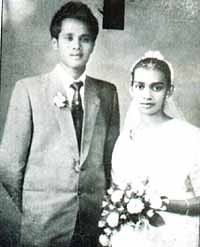

Freddie with his wife Kamala |

by Revata Silva

There was a time when everyone knew Freddie Silva, a time when he was not only

the undisputed vikata raja of Sinhala cinema but when there would have been thousands

ready to come to his side in times of need and thousands and thousands to lament should he

have died. Times change, and Freddie died impoverished. He went quietly, his death was not

considered to be newsworthy. Sarasaviya, the country’s main Sinhala film weekly which

had awarded him with the once-in-a-lifetime Ranathisara award in 1989, dedicated only a

single page to assess the work of this remarkable actor, singer and film producer.

Freddie was a phenomenal cinema comedian and a singer of rare quality. Freddie had appeared in over 300 of the 850 films screened in the first fifty years of Sinhala cinema. I met this man who thrilled an entire nation for almost thirty years just a month before he died. I found him not in a plush mansion fitting his celebrity status but in broken down garage down Emmanuel Church Road, Rawatawatte, which was his bedroom, TV room and kitchen. I talked with a lonely man, floundering in destitution. He was pensive, limping slightly and it was in a weak voice that he traced the trajectories of his eventful and in many ways tragic life.

Freddie was born in 1938 in Puvakaramba, Moratuwa and was christened Halpeliyanage Morris Joseph de Silva. He was the only child in the family. His father was an overseer in the Moratuwa Urban Council. His mother was a dedicated member of the Salvation Army. Freddie, however, was far from religious. He only loved singing and dancing, especially at parties. His father, apparently, used to punish him for not attending school. Naturally, it was a party that propelled him to stardom.

"In the late fifties, my relative Aelien Perera took me to the birthday party of Sir John Kotelawala. I presented my famous song, bar, bar, bar, bar eken beela (written by Alanson Mendis) with a dance." The crowd had danced with Freddie and the Premier had asked Freddie, "Ey kollo, umbe kakul wala spring hai koralada?" (Boy are your legs fixed with springs?). "Sir John threw me into the middle of a bunch of girls. I whispered to him that I was looking for a job. He said that I was not fit for any job but singing."

Freddie had then met Livy Wijemanne of Radio Ceylon, carrying a letter of recommendation from Sir John. The first song he recorded was mottapala. This was followed by his famous bar song to a melody composed by P. L. A. Somapala.

Freddie’s partnership with Premakirthi de Alwis, the slain lyricist, set a new trend in Sinhala song history, that of the satirical song. "Aron Mama", "Pankiritta", "Nedeyo", "Handa Mama", "Kekille Rajjuruwo", "Parana Coat" (In the film "Lokuma Hinawa") were satirical comments on social injustice. He was never hailed as a classical singer, but his unique ability was unquestioned. In particular, "Kundumani", the highlight of his singing career, it is said would have elicited a gasp from any Karnatic music pundit, for he had sung it to perfection.

"I liked to act from my small days. I got together with some other village boys and made two short plays named ‘Avathara Ellima’ and ‘Magadi’. We charged 25 cents from those who came to see those plays. They booed us and we threw kukul sayam at them. Later we got punished by our parents," Freddie reminisced on his early beginnings as an artist.

He explained how he shifted gear to join the silver screen. "I shared a room with Jothipala at Quarry Road, Dehiwala. Roy de Silva was also with us. When we were at Maradana, Jothi, Milton Perera and I went to sing at parties. Through friends like Cyril A. Seelawimala and Lal Heenetigala, I was introduced to K. A. W. Perera who was then co-directing the film "Suhada Sohoyuro" with L. S. Ramachandran. This was in 1963."

His cinema debut, a dance in the beach with Vijitha Mallika singing the famous "Diya rella verale hapi hapi" made a remarkable impression. "I was firstly given a comedy character which I did well. Then onwards I automatically became a comedian. Those days we worked together very closely. Sandya Kumari, Vijitha Mallika and Desi Akka (Rukmani Devi) helped me a lot. I performed serious roles in ‘Sekaya’ (’65), ‘Lasanda’ (’74) and ‘Sukiri kella’ (’75). The most memorable role I played was in ‘Sukiri kella’. That was of a mentally handicapped boy. Prior to taking up the role , I studied the behaviour of a real such boy who lived at Koralawella.

By the eighties, he was the number one comedian and film producers were reluctant to make a film without Freddie for fear of a financial flop. His mere appearance on the screen left crowds in fits of laughter. Of the 26 films released in 1992, he acted in 15, surely an unprecedented feat.

It was as though Freddie epitomised the ideal expressed in Omar Khayyam’s immortal lines:

A book of verse underneath the bough,

a jug of wine, a loaf of bread - and thou

beside me singing in the wilderness -

and wilderness were Paradise enow.

"I didn’t have even five minutes of rest those days. Dubbing to shooting and shooting to dubbing. From this studio to that. It was a wonderful time. I earned money, but never saved. I ate and drank. Wherever we went, there was liquor."

M. S. Fernando’s "Mal yahanavaki loke" which he sang for the film "Singappuru Charlie" emphasises this life style. There was plenty of money, "beautiful" and "open-hearted" women and bottles of whisky and arrack. The majority of the artistes were traditionalists in social view and realists from the point of view of art. They were not mature capitalists.

Things changed and so rapidly that Freddie himself was at a loss to explain the radical transformation in his life. "I am not taken for anything these days. I don’t worry too much because I did all the nineteen of the eighteen things in life (keli daha aten daha navayama keruwa). I have no work now. I have a Rs. 2000 pension from the Film Corporation. Believe me, there are days when I have nothing to eat. There is a Muslim businessman who gives me money on a monthly basis. He heard about my plight through the TV. If not for him I would now be dead."

"If Vijaya (Kumaratunga), Jothipala or President Premadasa were living, my destiny would have been quite different. I acted with Vijaya in nearly ten films, the last one being "Yukthiyada shakthiyada" (’87). I still remember the day I saw his face at the Accident Ward after being shot. I failed and fell into the arms of Vincent Karu. That marked the decline of our cinema. That’s the way of life, thiyanakota hondai, nethi daata ivarai."

Freddie was not a solitary victim of a kind of lifestyle and world view that went out of fashion. There were other extremely talented artistes who suffered psychologically and died relatively young. Many of them were victims of cirrhosis. Many lost the love of family and spent their last days with distant people or in hospitals or homes for the elderly. Jothipala, Clarence Wijewardena, Milton Mallawarachchi, Milton Perera, M. S. Fernando, C. T. Fernando, Ananda Jayaratne and others to a greater or lesser extent suffered like Freddie did.

Today’s artistes are a different breed altogether. Freddie drank, Tennyson Cooray does not; Ananda Jayaratne drank, Sanath Gunatilleke does not; Clarence drank but Rookantha does not; Gunadasa Kapuge drinks, Divulgane does not. Looks like there is politics in boozing. Whereas we saw artistes in an earlier era, today we see investors. The former lived in art, for the latter art provided a living. Yesterday we saw the original, pure, inherent art of Saraswathi Devi, and today we see rationally constructed, commercially motivated, surface art.

Whoever looks back at Freddie’s life and takes it as the sad destiny of one man, is but offering a purely symptomatic reading of a broader socio-economic reality. Freddie’s life exposes the gravely inhuman parameters of the present system which uses your capacity and talent to activate and sustain itself but has no space or a sense for welfare, and retreats once you are incapable or incapacitated. Human life, in a context lacking collective social feeling, grooms only individuality and personal glory. Art, it follows, can be nothing more than a money-oriented, individualistic and commercial endeavour. The Freddie Silvas of such a creative climate are necessarily outcasts.

Freddie Silva believed that the society which he entertained with abandon would in return look after him in his time of need. He was completely neglected. All the laughs his insatiable sense of humour generated were responded to with silence. He was left in shock, despair and anguish and died a solitary death. We are, sadly, and as Freddie realised too late, are a gunamaku (ungrateful) society.